Anatoly Zinovievich Itkin was born in Moscow on January 28, 1931. He graduated from art school in Moscow in 1950, after which he enrolled in the graphics faculty of the Moscow Surikov Art Institute.

Even before graduating from the institute, he began working as an illustrator for Moscow publishing houses, including Detskaya Literatura, Malysh, and Sovetskaya Rossiya.

Here's what the artist Nika Golts says about Anatoly Itkin:

I watched him work on illustrations for Jules Verne. Anatoly Itkin has a wonderful way of delving into the very essence of the author, into the very book he is illustrating at that moment. This is unmistakably Jules Verne, and no one else could have done it. Tolya decided to rework a picture because he didn't like the figure in the foreground, and behind it was a ship sailing up. It was tiny. And I said, “You can just redo it—erase the figure in the front and make a new one.” “No! Because over there—that little ship, and now I want it to be sailing up, not sailing away.” I said, “Well, what's the difference—it's a sail, what does it matter?” “No! The rigging is completely different! It has some kind of topgallant mast raised, but it should be lowered.” Well, in short, he knows everything. And it seems to me that this isn't some petty fastidiousness; on the contrary, it's a sign of a very great culture. As for culture in general, Anatoly Zinovievich is steeped in it to the bone. Both taste and culture are very high qualities of his. But what has always amazed me is his sense of responsibility, I suppose. He cannot do a bad job, he cannot be careless, he cannot do a half-hearted job.

In total, Itkin has illustrated over two hundred works of Russian and world literature. In 1998, he was awarded the title of Honored Artist of Russia.

By the way, you can find and buy a book with these illustrations online (it also includes The Fatal Eggs, also illustrated by him).

“And into the third apartment, they moved in housing-comrades.”

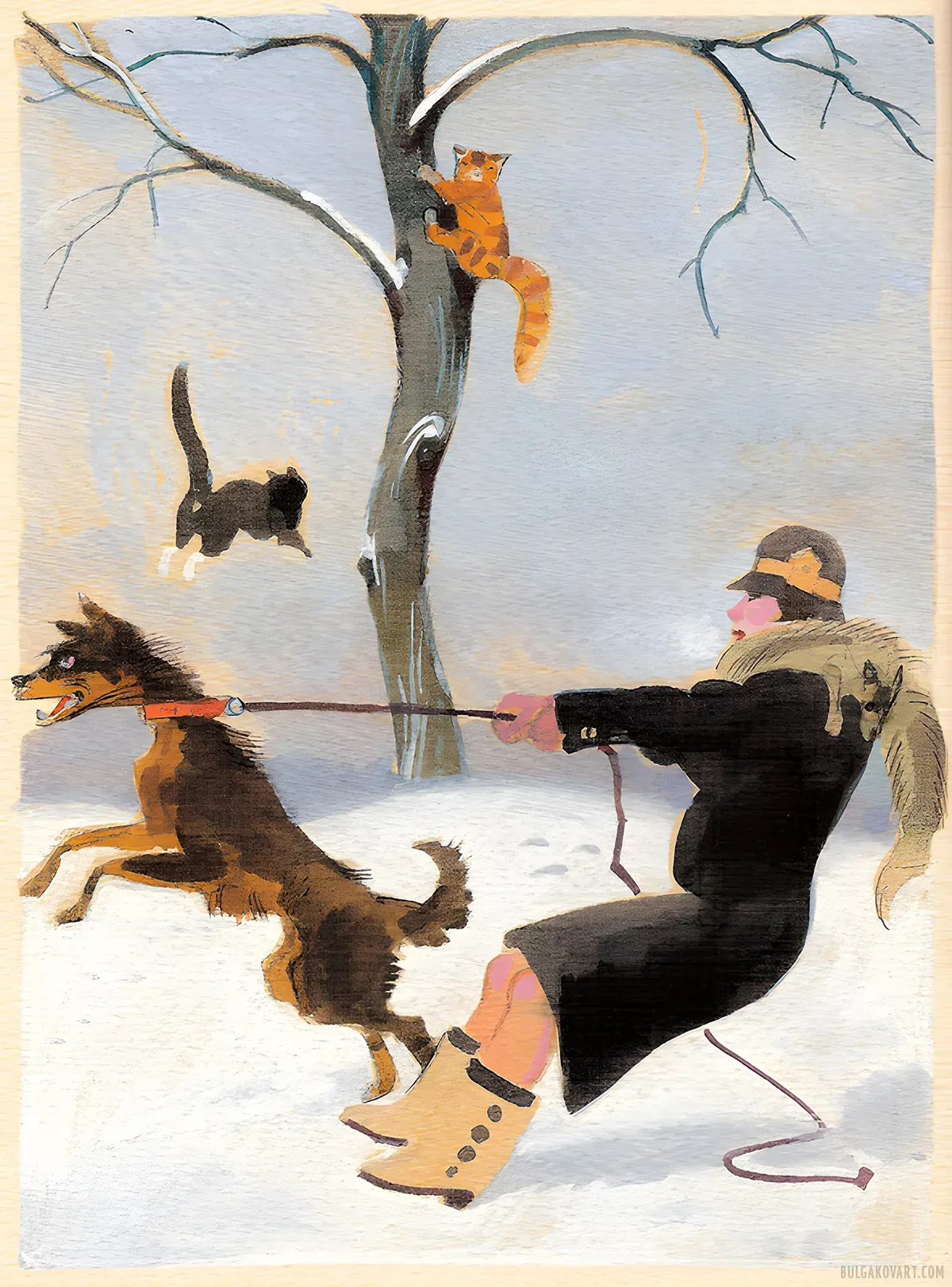

The important dog-benefactor spun around sharply on the step and, in horror, asked: “Well-l?”

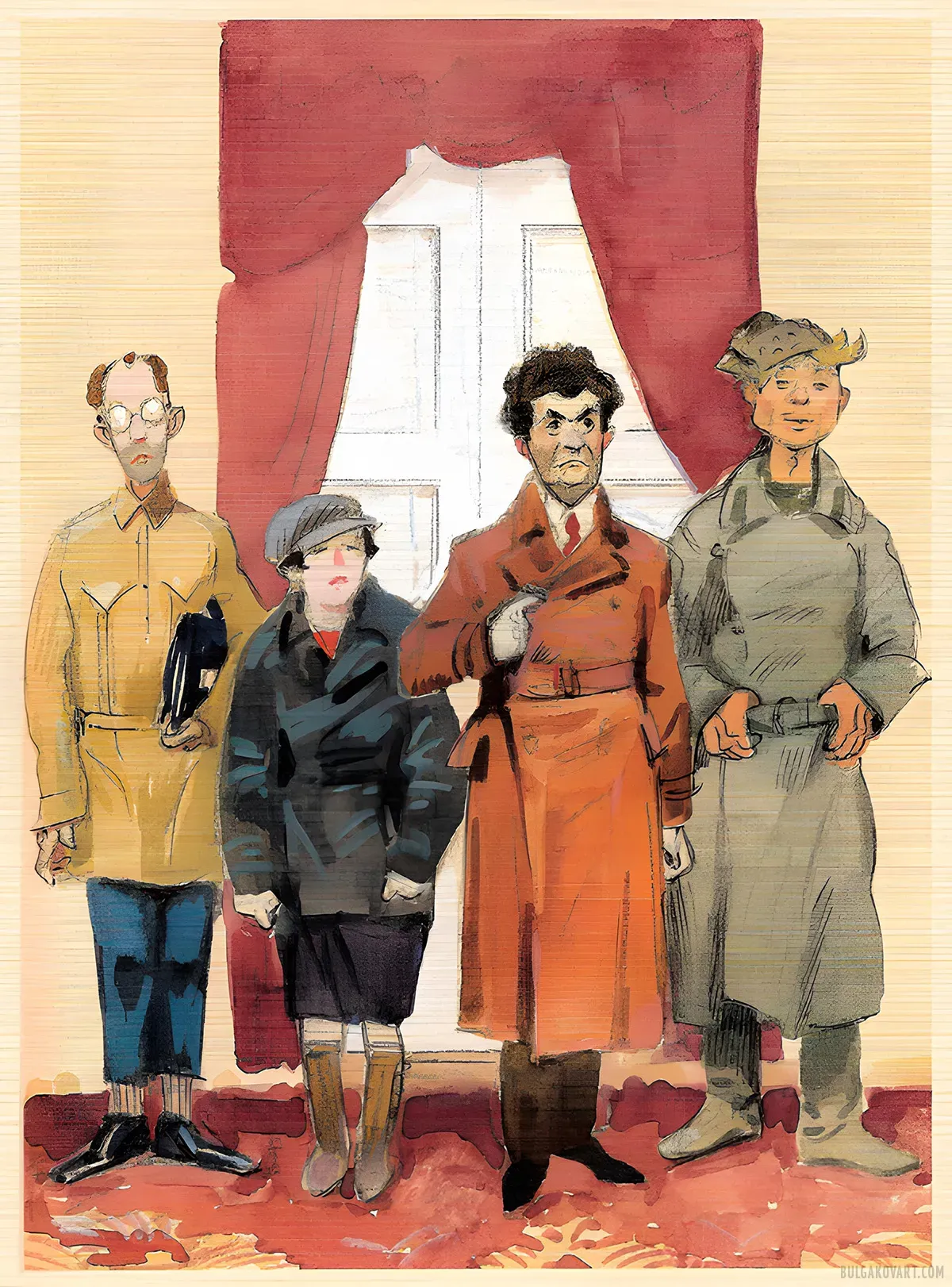

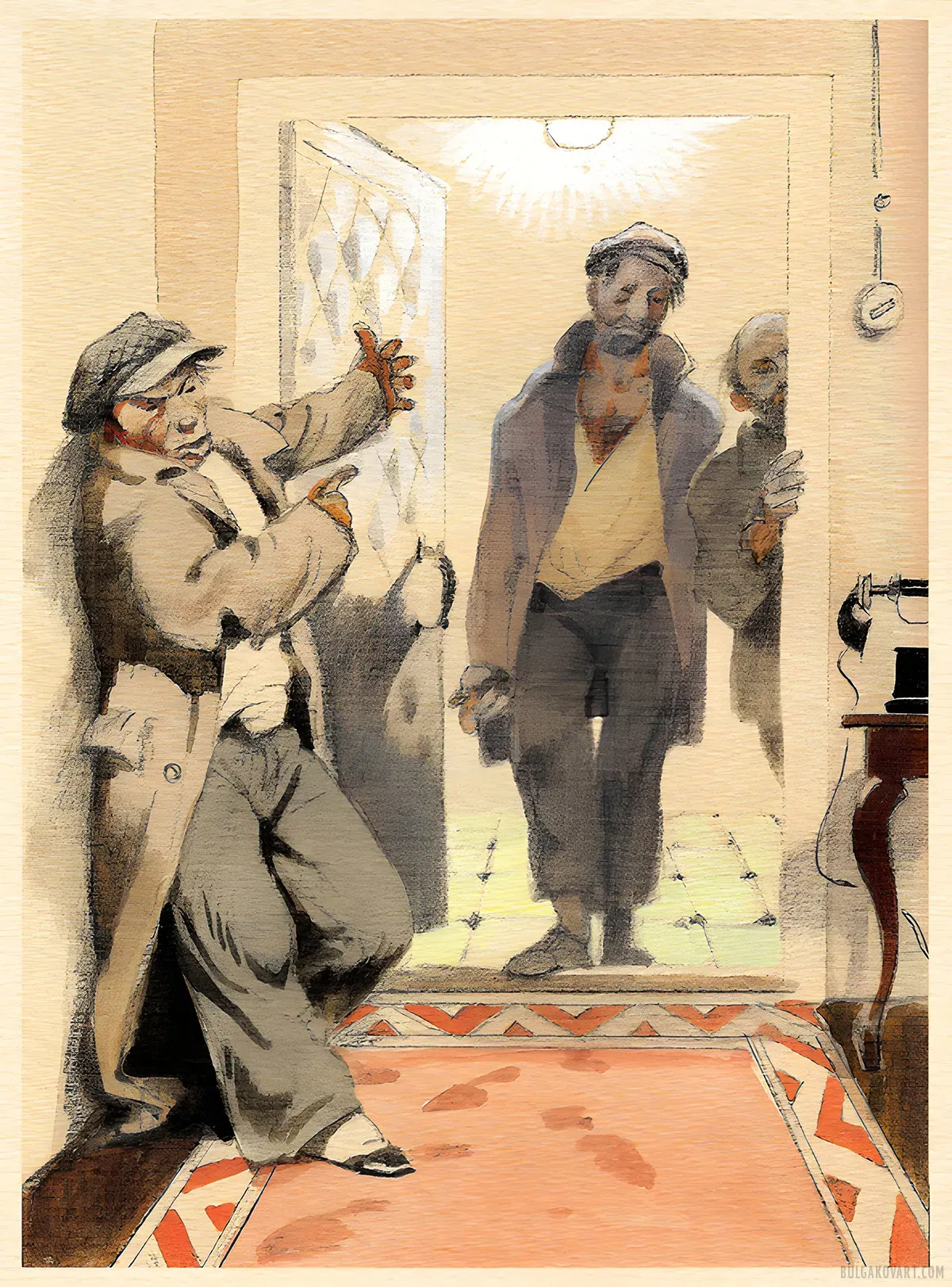

The door let in some unusual visitors. There were four of them at once. All young men, and all dressed very modestly.

“A collar is just like a briefcase,” the dog quipped to himself.

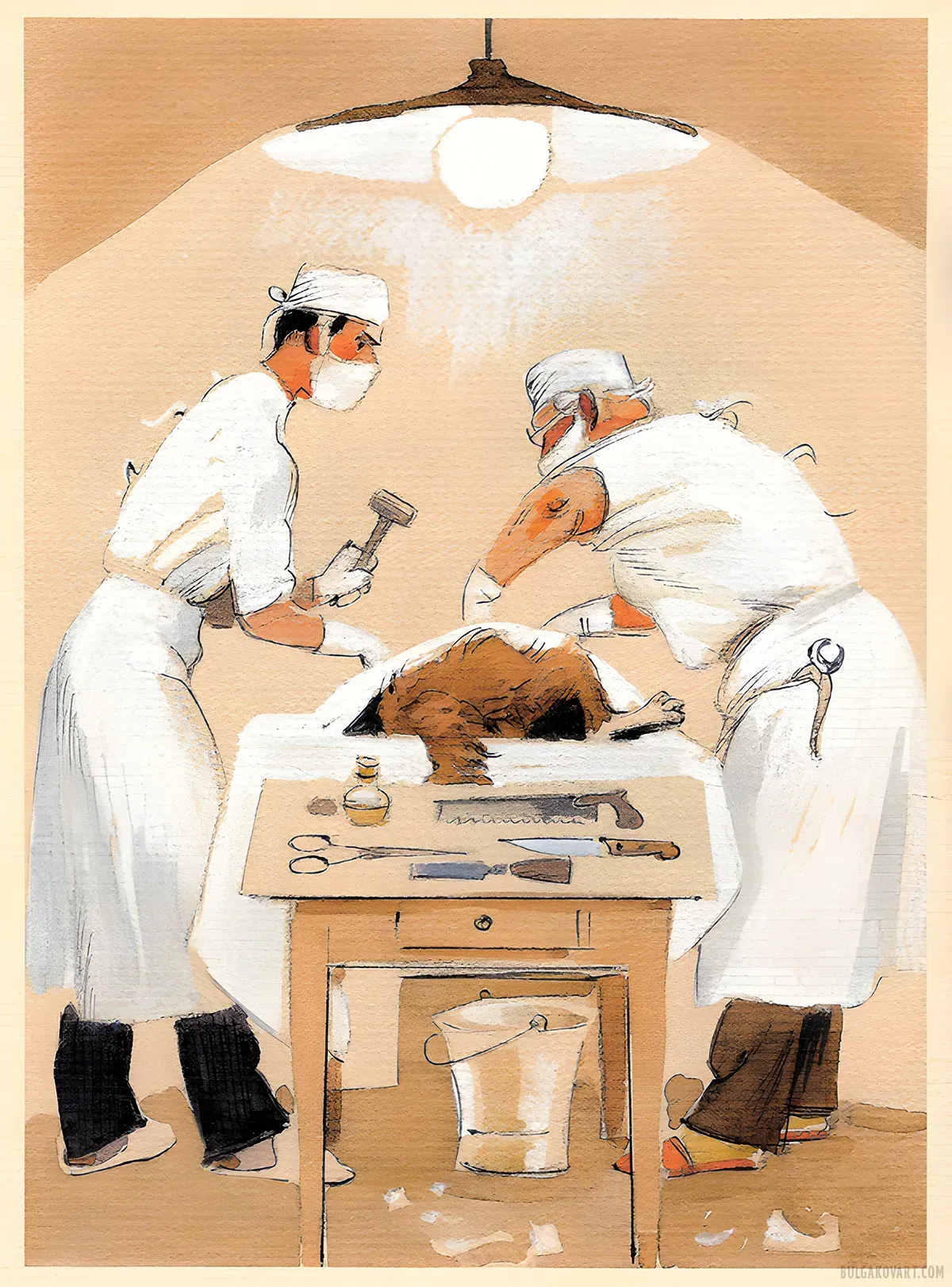

Filipp Filippovich's teeth clenched, his eyes took on a sharp, piercing glint, and with a flourish of his small knife, he made a long, accurate incision along Sharik's belly.

Doctor Bormental's notebook. In the notebook are some schematic drawings, by all indications depicting a transformation.

In the broken window near the ceiling, Poligraf Poligrafovich's mug appeared and poked into the kitchen. It was contorted, his eyes were tearful, and a scratch, flaming with fresh blood, ran down his nose.

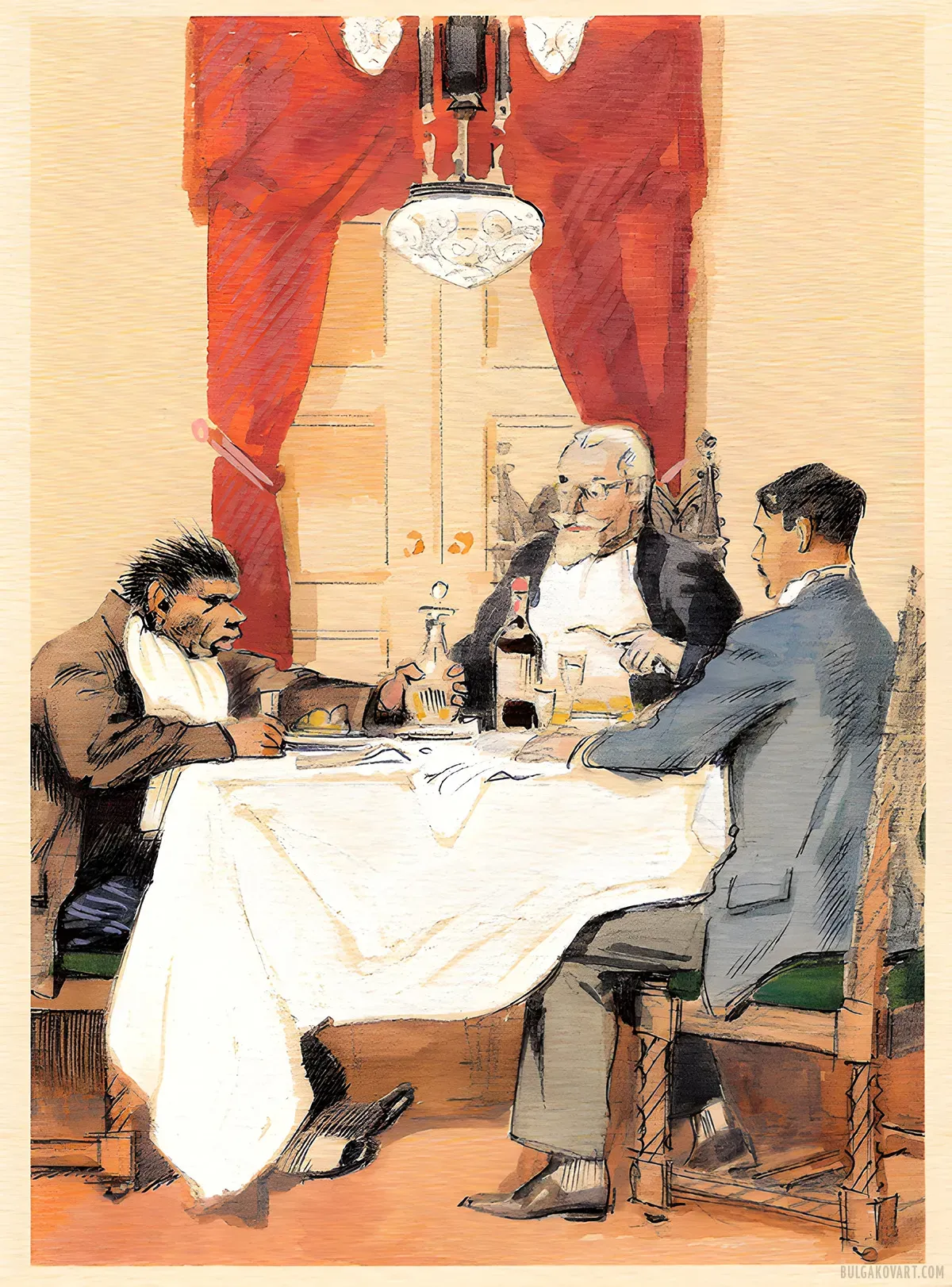

“Food, Ivan Arnoldovich, is a tricky thing. One must know how to eat, and, imagine that, most people don't know how to do it at all. One must not only know what to eat, but also when and how.” (Filipp Filippovich shook his spoon meaningfully.) “And what to talk about at the same time. Yes. If you care about your digestion, here's some good advice—don't talk about Bolshevism or medicine at dinner. And, for God's sake, don't read Soviet newspapers before lunch.”

Sharikov, reeling and clinging to fur coats, mumbled something about the people being unknown to him, but that they weren't any sons of bitches but were good people.

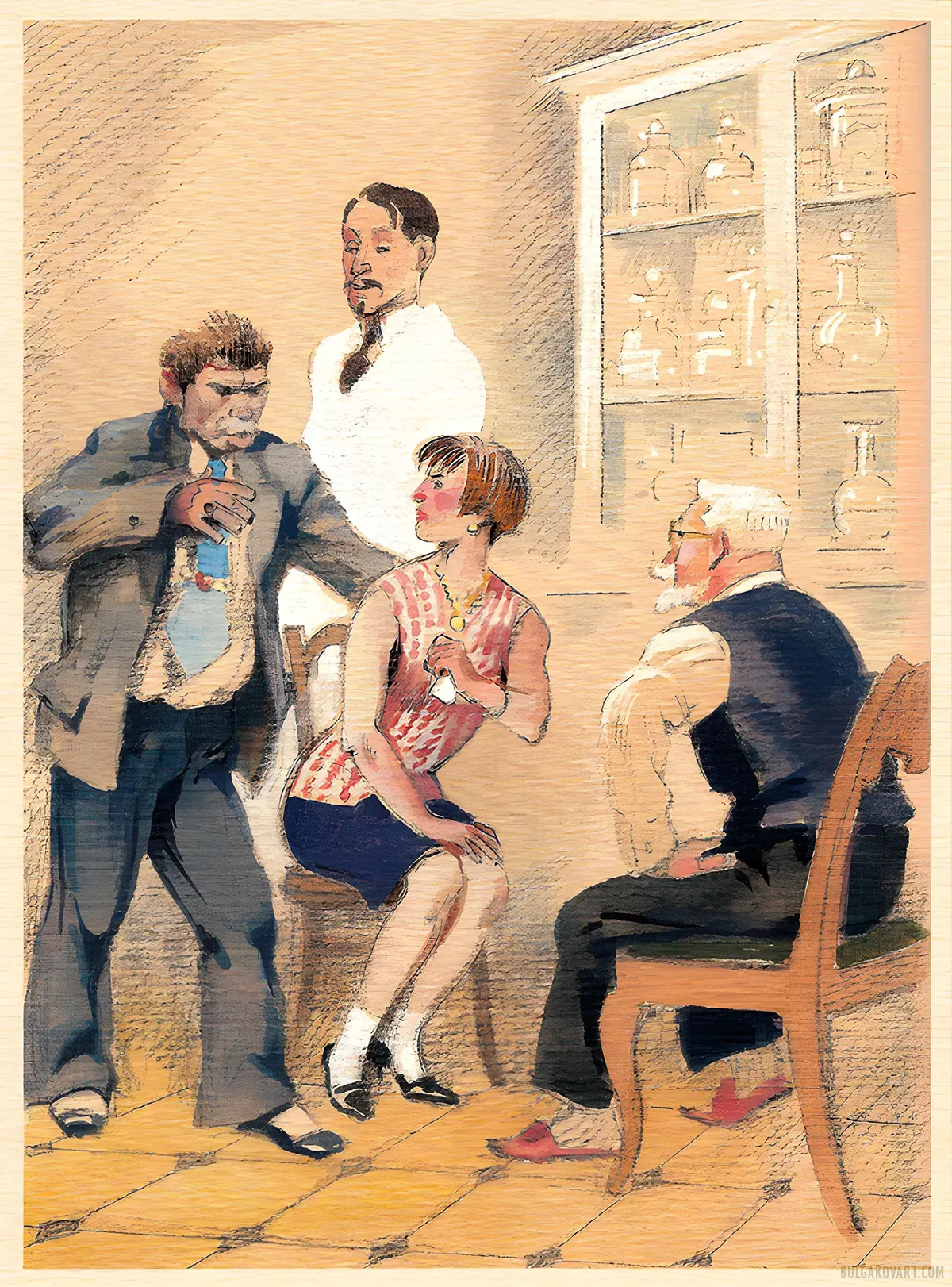

“I'm registering our marriage with her; she's our typist, and she's going to live with me. Bormental will have to be moved out of the reception room, he has his own apartment,” Sharikov explained with extreme hostility and a frown.

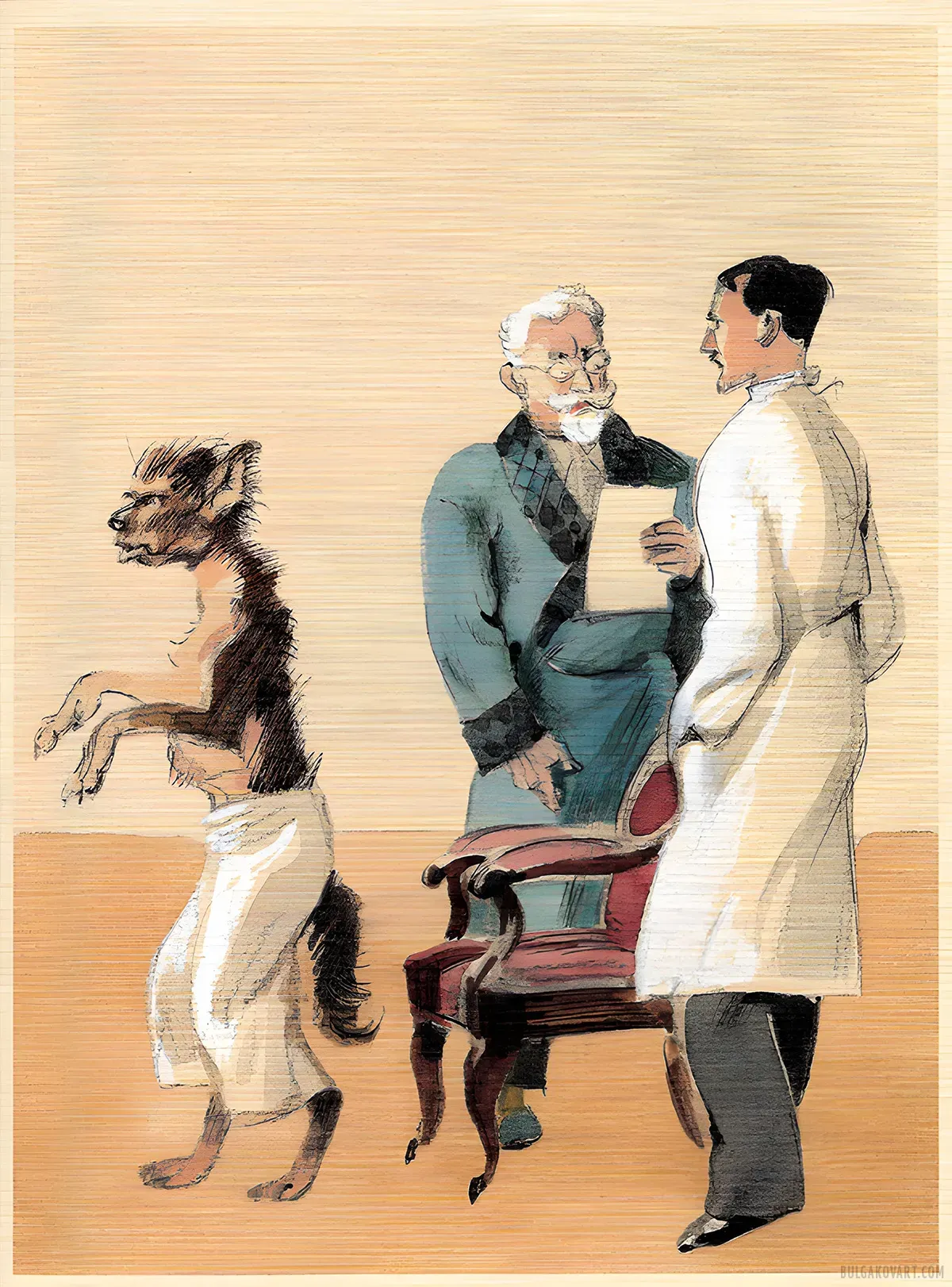

When Bormental returned and whistled, a dog of a strange quality jumped out of the study door. In some spots he was bald, and in other spots, his fur was growing back. He came out like a circus performer, on his hind legs, then got down on all fours and looked around.

The black man suddenly turned pale, dropped his briefcase, and started to fall to the side; the militiaman caught him from the side, and Fyodor from behind. A commotion ensued.

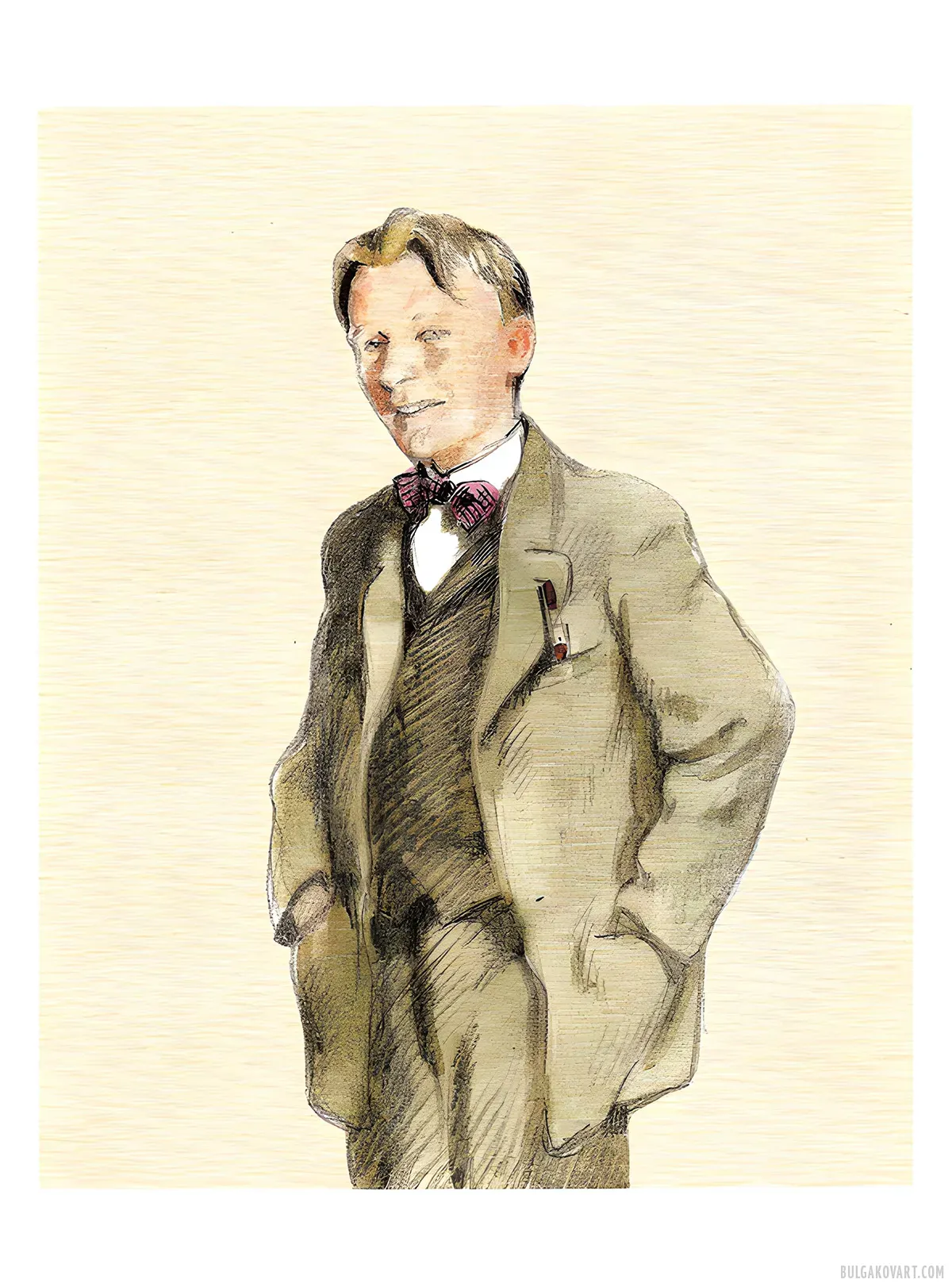

And in conclusion—a portrait of Bulgakov himself